Indie authors, these are the books that – probably – should not be published

My work as a publishing freelancer has brought me into contact with quite a few indie authors – or I should say, former indie authors, since I met most when they had accepted offers to work with a publishing house. So I know that many indies are great writers.

Incidentally, if you would find a definition of ‘indie authors’ useful here, this post by Paul White explains indies of all types.

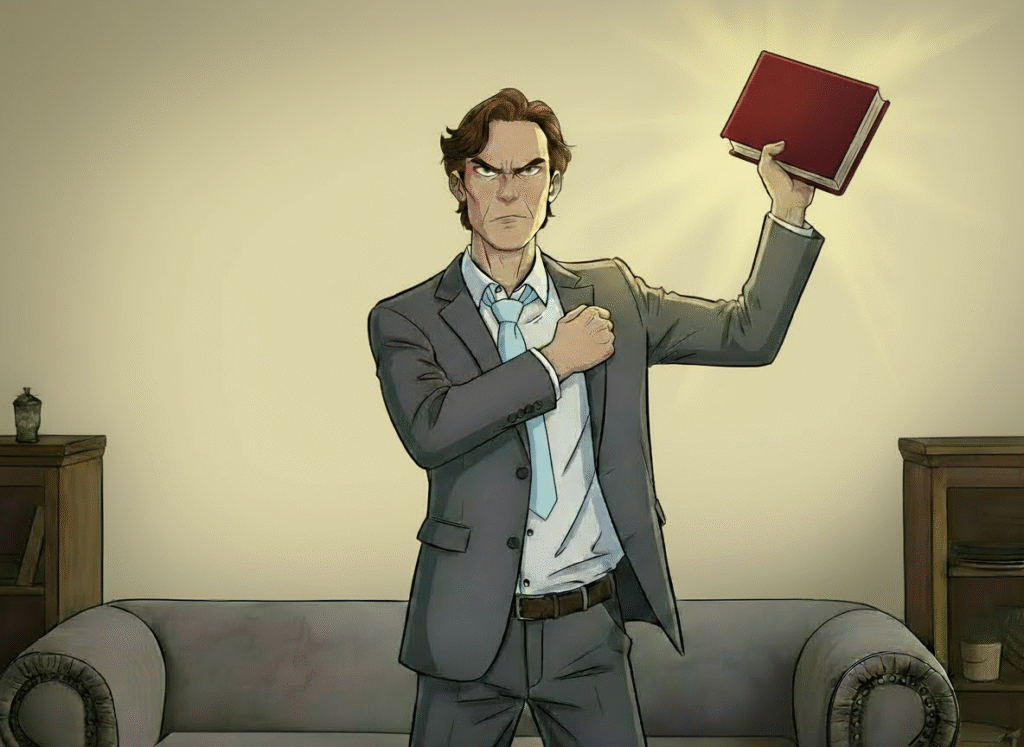

However, while most indie authors are actively promoting the best interests of literature, I have – several times – encountered amongst them a worrying genre that I call ‘the avenging work’. Avenging works are those that are an author writes and publishes (often self-publishes) primarily to (a) hurt somebody or (b) assert the author’s views on some relational difficulty, often to limit or avoid accountability. Or both.

These are the books that people write, from a very singular perspective, about an interpersonal dispute or rupture, such as divorce or separation. The novel based on a fight between siblings over a parent’s will. Articles reflecting on a lifetime of disappointment with wives/husbands/partners/parents/whatevers, which focus on the price the virtuous author has paid for those people’s shortcomings. Poetry about the injustice of redundancy (yes, really).

Avenging works are first cousins to misery lit, which I describe in another blog post.

Memoirs and criticism are not avenging works

It is important to note that memoirs, biographies and factual or fictionalised books about scandals/fraud/crime are very rarely avenging works. This is so even when they are laced with witty barbs and criticisms (as the best ones often are). Avenging works are written primarily and consciously to portray events in a way that denigrates one party and lauds another.

Not that this actually works, of course.

Presumably, many authors of avenging works believe publication will give them an audience. And that their audience will affirm the author’s righteousness. But neither of these things is true. Wordsrated.com reports that the average self-published book sells 250 copies. Since we know that some indie authors sell many more books than this, common sense dictates that lots sell fewer. And passionate writing does not guarantee sympathy from readers. The act of berating another person in public is ethically equivocal, to say the least.

In other words, avenging works may not deliver the fame and affirmation their authors want.

But sales figures are the least of such authors’ worries. Because publishing avenging works, especially as an indie author, is dangerous. Let me tell you a story . . .

UK law as applied to indie authors

Back in 2018, scandal rocked the Hertfordshire town of Broxbourne. A 66-year-old nurse poured weedkiller over her sister’s beloved artichokes. She also self-published a book, Behind the Artichokes, containing various allegations. The author was consequently hauled into court under the Malicious Communications Act. She pleaded not guilty and was cleared of all charges, but the scandal’s effects linger. The fact that I remember it more than seven years on is telling.

In this case, I am almost as offended by the heinous treatment of apostrophes on the back cover as I am by the book itself. But the principle stands. If you want to read more about this case (and see that back cover), the Hertfordshire Mercury coverage is still online. The story even made the BBC website.

Malicious Communications Act cases usually involve emails, texts, letters and social media posts, but the Act can apply to any text. And the potential for harm through literature does not end there.

Writers of avenging works might face action for defamation (lawyers Pinsent Masons explain the UK law on defamation in this guide); malicious falsehood (Pinsent and Masons describe the UK’s malicious falsehood laws here); harassment (read more here); or for breaches of UK privacy law (more here).

And that’s before we consider what blasting an enemy in print does for a writer’s credibility, reputation and relationships. Some may even face disciplinary action at work.

Keep it classy, indie authors

The vast majority of indie authors do not self-servingly air their dirty laundry in copy. I know this because I read their work.

Furthermore, I can empathise with people who consider expressing their sense of rage and injustice in text. Sometimes life does that. In moments of high emotion I have (fleetingly!) considered it myself.

But then I remember that such revenge rarely works. And when it does work, it helps if the writer is genius (which I, manifestly, am not). For example, Dante consigned loads of his enemies to Hell in The Divine Comedy, and that has had an audience for more than 700 years.

But for the rest of us, there is much to recommend emotional management and personal dignity. I believe that self regulation is a superpower, and even if I am wrong, at least it keeps the lawyers away!

Comments are closed